Books, and the stories they contained, were the only things I felt I was able to possess as a child. Even then, the possession was not literal; my father is a librarian, and perhaps because he believed in collective property, or perhaps because my parents considered buying books for me an extravagance, or perhaps because people generally acquired less then than they do now, I had almost no books to call my own. I remember coveting and eventually being permitted to own a book for the first time. I was five or six. The book was diminutive, about four inches square, and was called “You’ll Never Have to Look for Friends.” It lived among the penny candy and the Wacky Packs at the old-fashioned general store across the street from our first house in Rhode Island. The plot was trite, more an extended greeting card than a story. But I remember the excitement of watching my mother purchase it for me and of bringing it home. Inside the front cover, beneath the declaration “This book is especially for,” was a line on which to write my name. My mother did so, and also wrote the word “mother” to indicate that the book had been given to me by her, though I did not call her Mother but Ma. “Mother” was an alternate guardian. But she had given me a book that, nearly forty years later, still dwells on a bookcase in my childhood room.

Our house was not devoid of things to read, but the offerings felt scant, and were of little interest to me. There were books about China and Russia that my father read for his graduate studies in political science, and issues of Time that he read to relax. My mother owned novels and short stories and stacks of a literary magazine called Desh, but they were in Bengali, even the titles illegible to me. She kept her reading material on metal shelves in the basement, or off limits by her bedside. I remember a yellow volume of lyrics by the poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, which seemed to be a holy text to her, and a thick, fraying English dictionary with a maroon cover that was pulled out for Scrabble games. At one point, we bought the first few volumes of a set of encyclopedias that the supermarket where we shopped was promoting, but we never got them all. There was an arbitrary, haphazard quality to the books in our house, as there was to certain other aspects of our material lives. I craved the opposite: a house where books were a solid presence, piled on every surface and cheerfully lining the walls. At times, my family’s effort to fill our house with books seemed thwarted; this was the case when my father mounted rods and brackets to hold a set of olive-green shelves. Within a few days the shelves collapsed, the Sheetrocked walls of our seventies-era Colonial unable to support them.

What I really sought was a better-marked trail of my parents’ intellectual lives: bound and printed evidence of what they’d read, what had inspired and shaped their minds. A connection, via books, between them and me. But my parents did not read to me or tell me stories; my father did not read any fiction, and the stories my mother may have loved as a young girl in Calcutta were not passed down. My first experience of hearing stories aloud occurred the only time I met my maternal grandfather, when I was two, during my first visit to India. He would lie back on a bed and prop me up on his chest and invent things to tell me. I am told that the two of us stayed up long after everyone else had gone to sleep, and that my grandfather kept extending these stories, because I insisted that they not end.

Bengali was my first language, what I spoke and heard at home. But the books of my childhood were in English, and their subjects were, for the most part, either English or American lives. I was aware of a feeling of trespassing. I was aware that I did not belong to the worlds I was reading about: that my family’s life was different, that different food graced our table, that different holidays were celebrated, that my family cared and fretted about different things. And yet when a book was in my possession, and as I read it, this didn’t matter. I entered into a pure relationship with the story and its characters, encountering fictional worlds as if physically, inhabiting them fully, at once immersed and invisible.

In life, especially as a young girl, I was afraid to participate in social activities. I worried about what others might make of me, how they might judge. But when I read I was free of this worry. I learned what my fictional companions ate and wore, learned how they spoke, learned about the toys scattered in their rooms, how they sat by the fire on a cold day drinking hot chocolate. I learned about the vacations they took, the blueberries they picked, the jams their mothers stirred on the stove. For me, the act of reading was one of discovery in the most basic sense—the discovery of a culture that was foreign to my parents. I began to defy them in this way, and to understand, from books, certain things that they didn’t know. Whatever books came into the house on my account were part of my private domain. And so I felt not only that I was trespassing but also that I was, in some sense, betraying the people who were raising me.

When I began to make friends, writing was the vehicle. So that, in the beginning, writing, like reading, was less a solitary pursuit than an attempt to connect with others. I did not write alone but with another student in my class at school. We would sit together, this friend and I, dreaming up characters and plots, taking turns writing sections of the story, passing the pages back and forth. Our handwriting was the only thing that separated us, the only way to determine which section was whose. I always preferred rainy days to bright ones, so that we could stay indoors at recess, sit in the hallway, and concentrate. But even on nice days I found somewhere to sit, under a tree or on the ledge of the sandbox, with this friend, and sometimes one or two others, to continue the work on our tale. The stories were transparent riffs on what I was reading at the time: families living on prairies, orphaned girls sent off to boarding schools or educated by stern governesses, children with supernatural powers, or the ability to slip through closets into alternate worlds. My reading was my mirror, and my material; I saw no other part of myself.

My love of writing led me to theft at an early age. The diamonds in the museum, what I schemed and broke the rules to obtain, were the blank notebooks in my teacher’s supply cabinet, stacked in neat rows, distributed for us to write out sentences or practice math. The notebooks were slim, stapled together, featureless, either light blue or a brownish-yellow shade. The pages were lined, their dimensions neither too small nor too large. Wanting them for my stories, I worked up the nerve to request one or two from the teacher. Then, on learning that the cabinet was not always locked or monitored, I began helping myself to a furtive supply.

In the fifth grade, I won a small prize for a story called “The Adventures of a Weighing Scale,” in which the eponymous narrator describes an assortment of people and other creatures who visit it. Eventually the weight of the world is too much, the scale breaks, and it is abandoned at the dump. I illustrated the story—all my stories were illustrated back then—and bound it together with bits of orange yarn. The book was displayed briefly in the school library, fitted with an actual card and pocket. No one took it out, but that didn’t matter. The validation of the card and pocket was enough. The prize also came with a gift certificate for a local bookstore. As much as I wanted to own books, I was beset by indecision. For hours, it seemed, I wandered the shelves of the store. In the end, I chose a book I’d never heard of, Carl Sandburg’s “Rootabaga Stories.” I wanted to love those stories, but their old-fashioned wit eluded me. And yet I kept the book as a talisman, perhaps, of that first recognition. Like the labels on the cakes and bottles that Alice discovers underground, the essential gift of my award was that it spoke to me in the imperative; for the first time, a voice in my head said, “Do this.”

As I grew into adolescence and beyond, however, my writing shrank in what seemed to be an inverse proportion to my years. Though the compulsion to invent stories remained, self-doubt began to undermine it, so that I spent the second half of my childhood being gradually stripped of the one comfort I’d known, that formerly instinctive activity turning thorny to the touch. I convinced myself that creative writers were other people, not me, so that what I loved at seven became, by seventeen, the form of self-expression that most intimidated me. I preferred practicing music and performing in plays, learning the notes of a composition or memorizing the lines of a script. I continued working with words, but channelled my energy into essays and articles, wanting to be a journalist. In college, where I studied literature, I decided that I would become an English professor. At twenty-one, the writer in me was like a fly in the room—alive but insignificant, aimless, something that unsettled me whenever I grew aware of it, and which, for the most part, left me alone. I was not at a stage where I needed to worry about rejection from others. My insecurity was systemic, and preëmptive, insuring that, before anyone else had the opportunity, I had already rejected myself.

For much of my life, I wanted to be other people; here was the central dilemma, the reason, I believe, for my creative stasis. I was always falling short of people’s expectations: my immigrant parents’, my Indian relatives’, my American peers’, above all my own. The writer in me wanted to edit myself. If only there was a little more this, a little less that, depending on the circumstances: then the asterisk that accompanied me would be removed. My upbringing, an amalgam of two hemispheres, was heterodox and complicated; I wanted it to be conventional and contained. I wanted to be anonymous and ordinary, to look like other people, to behave as others did. To anticipate an alternate future, having sprung from a different past. This had been the lure of acting—the comfort of erasing my identity and adopting another. How could I want to be a writer, to articulate what was within me, when I did not wish to be myself?

It was not in my nature to be an assertive person. I was used to looking to others for guidance, for influence, sometimes for the most basic cues of life. And yet writing stories is one of the most assertive things a person can do. Fiction is an act of willfulness, a deliberate effort to reconceive, to rearrange, to reconstitute nothing short of reality itself. Even among the most reluctant and doubtful of writers, this willfulness must emerge. Being a writer means taking the leap from listening to saying, “Listen to me.”

This was where I faltered. I preferred to listen rather than speak, to see instead of be seen. I was afraid of listening to myself, and of looking at my life.

It was assumed by my family that I would get a Ph.D. But after I graduated from college, I was, for the first time, no longer a student, and the structure and system I’d known and in some senses depended on fell away. I moved to Boston, a city I knew only vaguely, and lived in a room in the home of people who were not related to me, whose only interest in me was my rent. I found work at a bookstore, opening shipments and running a cash register. I formed a close friendship with a young woman who worked there, whose father is a poet named Bill Corbett. I began to visit the Corbetts’ home, which was filled with books and art—a framed poem by Seamus Heaney, drawings by Philip Guston, a rubbing of Ezra Pound’s gravestone. I saw the desk where Bill wrote, obscured by manuscripts, letters, and proofs, in the middle of the living room. I saw that the work taking place on this desk was obliged to no one, connected to no institution; that this desk was an island, and that Bill worked on his own. I spent a summer living in that house, reading back issues of The Paris Review, and when I was alone, in a bright room on the top floor, pecking out sketches and fragments on a typewriter.

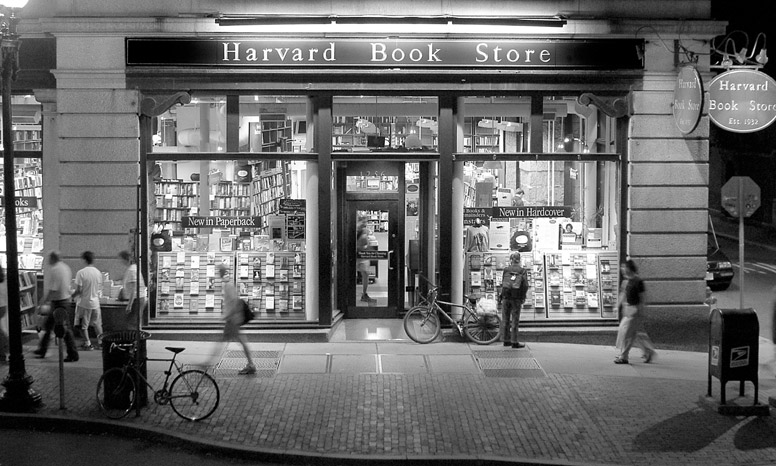

I began to want to be a writer. Secretly at first, exchanging pages with one other person, our prescheduled meetings forcing me to sit down and produce something. Stealing into the office where I had a job as a research assistant, on weekends and at night, to type stories onto a computer, a machine I did not own at the time. I bought a copy of “Writer’s Market,” and sent out stories to little magazines that sent them back to me. The following year, I entered graduate school, not as a writer but as a student of English literature. But beneath my declared scholarly objective there was now a wrinkle. I used to pass a bookshop every day on the way to the train, the storefront displaying dozens of titles that I always stopped to look at. Among them were books by Leslie Epstein, a writer whose work I had not yet read but whose name I knew, as the director of the writing program at Boston University. On a lark one day, I walked into the creative-writing department seeking permission to sit in on a class.

It was audacious of me. The equivalent, nearly two decades later, of stealing notebooks from a teacher’s cabinet; of crossing a line. The class was open only to writing students, so I did not expect Epstein to make an exception. After he did, I worked up the nerve to apply for a formal spot in the creative-writing program the following year. When I told my parents that I’d been accepted, with a fellowship, they neither encouraged nor discouraged me. Like so many aspects of my American life, the idea that one could get a degree in creative writing, that it could be a legitimate course of study, seemed perhaps frivolous to them. Still, a degree was a degree, and so their reaction to my decision was to remain neutral. Though I corrected her, my mother, at first, referred to it as a critical-writing program. My father, I am guessing, hoped it would have something to do with a Ph.D.

My mother wrote poems occasionally. They were in Bengali, and were published now and then in literary magazines in New England or Calcutta. She seemed proud of her efforts, but she did not call herself a poet. Both her father and her youngest brother, on the other hand, were visual artists. It was by their creative callings that they were known to the world, and had been described to me. My mother spoke of them reverently. She told me about the day that my grandfather had had to take his final exam at the Government College of Art, in Calcutta, and happened to have a high fever. He was able to complete only a portion of the portrait he had been asked to render, the subject’s mouth and chin, but it was done so skillfully that he graduated with honors. Watercolors by my grandfather were brought back from India, framed, and shown off to visitors, and to this day I keep one of his medals in my jewelry box, regarding it since childhood as a good-luck charm.

Before our visits to Calcutta, my mother would make special trips to an art store to buy the brushes and paper and pens and tubes of paint that my uncle had requested. Both my grandfather and my uncle earned their living as commercial artists. Their fine art brought in little money. My grandfather died when I was five, but I have vivid memories of my uncle, working at his table in the corner of the cramped rented apartment where my mother was brought up, preparing layouts for clients who came to the house to approve or disapprove of his ideas, my uncle staying up all night to get the job done. I gathered that my grandfather had never been financially secure, and that my uncle’s career was also precarious—that being an artist, though noble and romantic, was not a practical or responsible thing to do.

Abandoned weighing scales, witches, orphans: these, in childhood, had been my subjects. As a child, I had written to connect with my peers. But when I started writing stories again, in my twenties, my parents were the people I was struggling to reach. In 1992, just before starting the writing program at B.U., I went to Calcutta with my family. I remember coming back at the end of summer, getting into bed, and almost immediately writing the first of the stories I submitted that year in workshop. It was set in the building where my mother had grown up, and where I spent much of my time when I was in India. I see now that my impulse to write this story, and several like-minded stories that followed, was to prove something to my parents: that I understood, on my own terms, in my own words, in a limited but precise way, the world they came from. For though they had created me, and reared me, and lived with me day after day, I knew that I was a stranger to them, an American child. In spite of our closeness, I feared that I was alien. This was the predominant anxiety I had felt while growing up.

I was my parents’ firstborn child. When I was seven, my mother became pregnant again, and gave birth to my sister in November, 1974. A few months later, one of her closest friends in Rhode Island, another Bengali woman, also learned that she was expecting. The woman’s husband, like my father, worked at the university. Based on my mother’s recommendation, her friend saw the same doctor and planned to deliver at the same hospital where my sister was born. One rainy evening, my parents received a call from the hospital. The woman’s husband cried into the telephone as he told my parents that their child had been born dead. There was no reason for it. It had simply happened, as it sometimes does. I remember the weeks following, my mother cooking food and taking it over to the couple, the grief in place of the son who was supposed to have filled their home. If writing is a reaction to injustice, or a search for meaning when meaning is taken away, this was that initial experience for me. I remember thinking that it could have happened to my parents and not to their friends, and I remember, because the same thing had not happened to our family, as my sister was by then a year old already, also feeling ashamed. But, mainly, I felt the unfairness of it—the unfairness of the couple’s expectation, unfulfilled.

We moved to a new house, whose construction we had overseen, in a new neighborhood. Soon afterward, the childless couple had a house built in our neighborhood as well. They hired the same contractor, and used the same materials, the same floor plan, so that the houses were practically identical. Other children in the neighborhood, sailing past on bicycles and roller skates, took note of this similarity, finding it funny. I was asked if all Indians lived in matching houses. I resented these children, for not knowing what I knew of the couple’s misfortune, and at the same time I resented the couple a little, for having modelled their home on ours, for suggesting that our lives were the same when they were not. A few years later the house was sold, the couple moving away to another town, and an American family altered the façade so that it was no longer a carbon copy of ours. The comic parallel between two Bengali families in a Rhode Island neighborhood was forgotten by the neighborhood children. But our lives had not been parallel; I was unable to forget this.

When I was thirty years old, digging in the loose soil of a new story, I unearthed that time, that first tragic thing I could remember happening, and wrote a story called “A Temporary Matter.” It is not exactly the story of what had happened to that couple, nor is it a story of something that happened to me. Springing from my childhood, from the part of me that was slowly reverting to what I loved most when I was young, it was the first story that I wrote as an adult.

My father, who, at eighty, still works forty hours a week at the University of Rhode Island, has always sought security and stability in his job. His salary was never huge, but he supported a family that wanted for nothing. As a child, I did not know the exact meaning of “tenure,” but when my father obtained it I sensed what it meant to him. I set out to do as he had done, and to pursue a career that would provide me with a similar stability and security. But at the last minute I stepped away, because I wanted to be a writer instead. Stepping away was what was essential, and what was also fraught. Even after I received the Pulitzer Prize, my father reminded me that writing stories was not something to count on, and that I must always be prepared to earn my living in some other way. I listen to him, and at the same time I have learned not to listen, to wander to the edge of the precipice and to leap. And so, though a writer’s job is to look and listen, in order to become a writer I had to be deaf and blind.

I see now that my father, for all his practicality, gravitated toward a precipice of his own, leaving his country and his family, stripping himself of the reassurance of belonging. In reaction, for much of my life, I wanted to belong to a place, either the one my parents came from or to America, spread out before us. When I became a writer my desk became home; there was no need for another. Every story is a foreign territory, which, in the process of writing, is occupied and then abandoned. I belong to my work, to my characters, and in order to create new ones I leave the old ones behind. My parents’ refusal to let go or to belong fully to either place is at the heart of what I, in a less literal way, try to accomplish in writing. Born of my inability to belong, it is my refusal to let go. ♦

The Music of the Primes: Searching to Solve the Greatest Mystery in Mathematics by Marcus du Sautoy

The Music of the Primes: Searching to Solve the Greatest Mystery in Mathematics by Marcus du Sautoy